By Barnabas Esiet

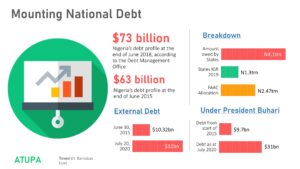

Nigeria’s debt profile, according to the Debt Management Office (DMO), stood at $73 billion (N22 trillion) at the end of June 2018 compared to $63 billion in June 2015. Available data has shown that the country’s external debt increased from $10.32 billion in June 30, 2015 to over $31 billion as at July 20, 2020.

The national debt, also called sovereign debt, is the sum total of the federal government’s obligations to its creditors, both local and foreign.

A breakdown indicates that the states are owing N4.1 trillion of the total debt stock even as these states’ total Internally Generated Revenue (IGR) in 2019 was barely N1.3 trillion, aside from the N2.47 trillion from the federal account allocation committee (FAAC).

Further analysis of the total national debt shows that external commitments, mostly commercial borrowings, grew by 114.05% in about three years from 2015 to 2018. Multilateral debt made up $10.88 billion or 49.28 percent of the country’s external debt profile in the period under review.

Brief History

From 1958, when Nigeria first obtained US$28 million for the construction of rail networks linking parts of the country, to 1977, records indicate that about 78.5 percent of the total national debt stock were mainly bilateral and multilateral loans with longer repayment periods and lower interest rates.

The first huge loan of US $1 Billion, referred to as jumbo loan, was sourced from the international capital market (ICM) in 1978 which then brought Nigeria’s total debt collection to about US$2.2 Billion.

Government thereafter went on a borrowing spree as loans from private commercial sources went up substantially while borrowings from bilateral and multilateral sources dipped .

In 2005, Nigeria’s external debt stood at $20.8 billion but went down to $3.5 billion by December 2006 after the country repaid its Paris Club debt.

Buying back the debt then was expected to provide a breather for funds to be channeled towards capital expenditure on infrastructure to facilitate economic growth and improvement in the living standard of the populace.

This, however, was not the case; the government instead increased recurrent expenditure while capital expenditure kept on declining as the country witnessed misappropriation and a lot of stolen wealth.

Years of lower oil prices, disproportionate spending and defense of the exchange rate has seen the debt situation somewhat back full circle as dead-weight borrowings increased while reproductive loans received less attention.

Under President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration, from the start of 2015, the nation’s external debt profile has risen from $9.7 billion to over $31 billion as at July 20, 2020.

These debts comprise; bilateral, multilateral, and commercial loans (Eurobonds and Diaspora bonds).

Implications for Businesses and the Populace

There’s no doubt that when national debt is within the threshold, government spending contributes to economic growth and improvement in quality of life, but when borrowings exceed the safe limits, experts say standard of living gradually declines following higher compensation demands by creditors for the fear they may not be repaid.

Experts have also warned that external debts have sociopolitical implications as loans, mostly from international financial institutions, come with tough conditions and open up the debtor’s economy to stringent control by the creditor country.

According to the experts, escalating national debt could lead to: weakened government ability to respond to socio economic problems, greater risk of fiscal crisis, lower income and national savings, higher interest payments, tax hikes and spending cuts

The collapse of the price of Nigeria’s mainstay, crude oil, compounded by poor economic policies, bad management, corruption and unfavorable terms of loan, have made it very difficult to service the mounting debt, particularly the commercial ones.

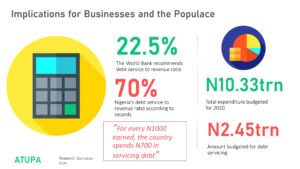

With declining annual revenue compared to expenditure, financial experts at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have warned that the country’s revenue-to-debt ratio is unsustainable and portends a serious concern for future generations of Nigerians.

The World Bank recommends debt service to revenue ratio of not more than 22.5%, however, records have shown that Nigeria’s debt service to revenue ratio is currently well over 70%, which means for every N1000 earned, the country spends N700 in servicing debt. Out of N10.33 trillion total expenditure budgeted for 2020, about 25% (N2.45 trillion) was allocated to debt servicing alone.

The government, in an effort to raise revenue mainly for servicing debts and spending on political office holders, has completely removed subsidy on petroleum products, increased the value added tax (VAT) from 5% to7.5% and pushed up electricity tariff by 70%.

Analysts are afraid that the country could soon become bankrupt and unable to meet its increasing obligations. This situation could cause socio economic upheaval with dire consequences for the country even as some trade unions have started protesting.

Muda Yusuf, the Director General of Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industries (LCCI), is worried that Nigeria may not be able to sustain the servicing cost of the growing debt. “How is the country going to meet up with other obligations?, that means a whole lot of other things including healthcare and social services will suffer because debt service is a first line charge.” He said.

Director General of LCCI, Muda Yusuf

As the Federal government continues to borrow, the country’s foreign reserves are being depleted to service the debt, inflation and taxes are also on the rise and the Naira is taking a beating as many Nigerians are daily finding it more difficult to afford the basic things of life.

Figures from the National Bureau of Statistics show that Nigeria’s annual inflation rate has risen to 13.22 percent in August 2020 from 12.82 percent in the previous month, even as more Nigerians are without jobs.

According to the Chief Executive officer of Carthena Advisory, Wole Ogundare, there is more to Nigeria being christened the poverty capital of the world.

CEO, Carthena Advisory, Wole Ogundare

“That single indicator of being the poverty capital of the world says a lot because the indicator is usually read across some sets of data, it’s not just that there’s no money, in terms of – security, infrastructure, GDP, employment, socioeconomic well being – if you look at it all across these indices including education and earnings it’s poor.” He noted.

Some worry that excessive government debt levels can impact economic stability with ramifications for unemployment and the well-being of Nigerians.

Nerus Ekezie, the Ag. Executive Director/CEO, IoD Center for Corporate Governance and a former Director at NASME, says Nigeria’s foreign and domestic debt profile is worrisome.

Ag. Executive Director/CEO, IoDCCG, Nerus Ekezie

“It is quite worrisome because of the rate commercial loans are rising almost on a daily basis and this has a corresponding effect on the economic growth of the nation and the well-being of taxpayers, more so as the funds are not being applied productively to develop assets.”Ekezie warned.

Bottom line

Some experts have suggested financial prudence on the part of the government, diversification of the economy and cutting down dependence on foreign goods and services as a way out of the debt imbroglio. Others have called on the federal government to place a premium on developing the local industry through better policy framework and enhanced financial incentives to the MSMEs.

According to Yusuf, “We need to create the right type of environment for private sector capital to come into some of the projects to reduce the burden on government spending on various infrastructure investments.”

In the same vein, Ekezie argues that if the current manufacturing capacity is improved, dependency on imported components of the economy will reduce as the government steps up it’s intervention in the various sectors of the economy.

“Government should harmonize the intervention funds and deploy them in financial institutions with the capacity to lend to deserving SMEs.” He advised.

For Ogundare, if we don’t first define the identity of the nation, then the government would not be able to channel the borrowings appropriately “If you look at Dubai for instance you see tourism,when you spend money you want to look forward to generating more money quickly, aside from crude oil, where’s the concentrated nerve center that can help Nigeria generate funds to repay the huge debts? He queried.

**This report was facilitated by the US Embassy and Civic Hive through the Atupa Fellowship Programme.

Comment here